By: Joy O'Brien on Oct 4, 2016

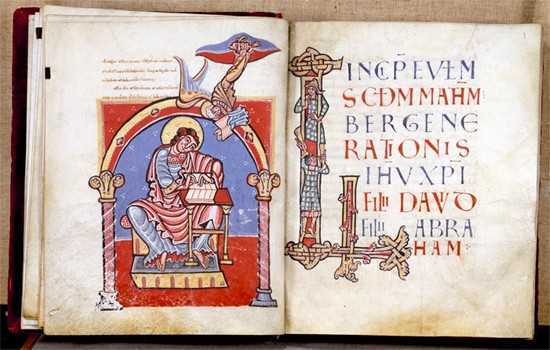

We’re excited to introduce Walters Ex Libris, a project that has been in the works for about a decade (however our involvement was just over the last couple years). The Walters Art Museum, located in Baltimore, has a considerable collection of ancient manuscripts dating from the 8th to the 20th century. By digitizing the manuscripts under a Creative Commons 3.0 license, they’re breaking new ground and offering an extraordinary level of detail about each work to researchers and curiosity-seekers alike, completely royalty-free. Already The Walters is seeing published works featuring imagery from their digitized manuscripts.

When Byte was pulled in, many of the digitized manuscripts were already online, however they were in what appeared to be an FTP site from the 90’s. It was our goal to make the manuscripts easy to search and browse for both researchers and general curiosity-seekers. We also felt it was important to make them interactive and explorable— to design an interface that gets out of the way of the user and lets them dive down a rabbit-hole of beautiful manuscripts.

This project was a perfect fit for us because it combined a number of our favorite things: a challenging set of data, beautiful cultural treasures, and a vision to freely share incredible cultural treasures with the world. Read their press release here.

Beautiful, complicated data

From the way I’ve described the project so far, you might imagine that it was a sunny walk in the park, but I would be doing Adam (developer) and myself a huge disservice if I didn’t tell you: That manuscript data was BEASTLY. It was completely wild. Inconsistencies everywhere, and not at the fault of anyone— as a sequential, yet historical document, it was just complex. It was our job to tame it, making a consistent user experience with an interface, and it was no easy feat.

I’ll give you an example. You’d think the first segment of pages in any given manuscript would be “chapter #1” (or psalm, or poem, etc). However these manuscripts aren’t just texts, they’re historical documents, and boy, the original owners of these pieces did whatever they wanted with their manuscripts. Maybe it got reordered to suit the reader better, or it all fell apart and got stitched back together later. Whatever the case, some of the manuscripts had both an original order and a current order, and we had to make an interface that accounts for both.

It was only through a ton of deep data exploration, great inter-team communication and a series of low-fidelity prototypes that we were able to build a browsing interface that makes it all look so consistent and easy.

Designing a useful search system

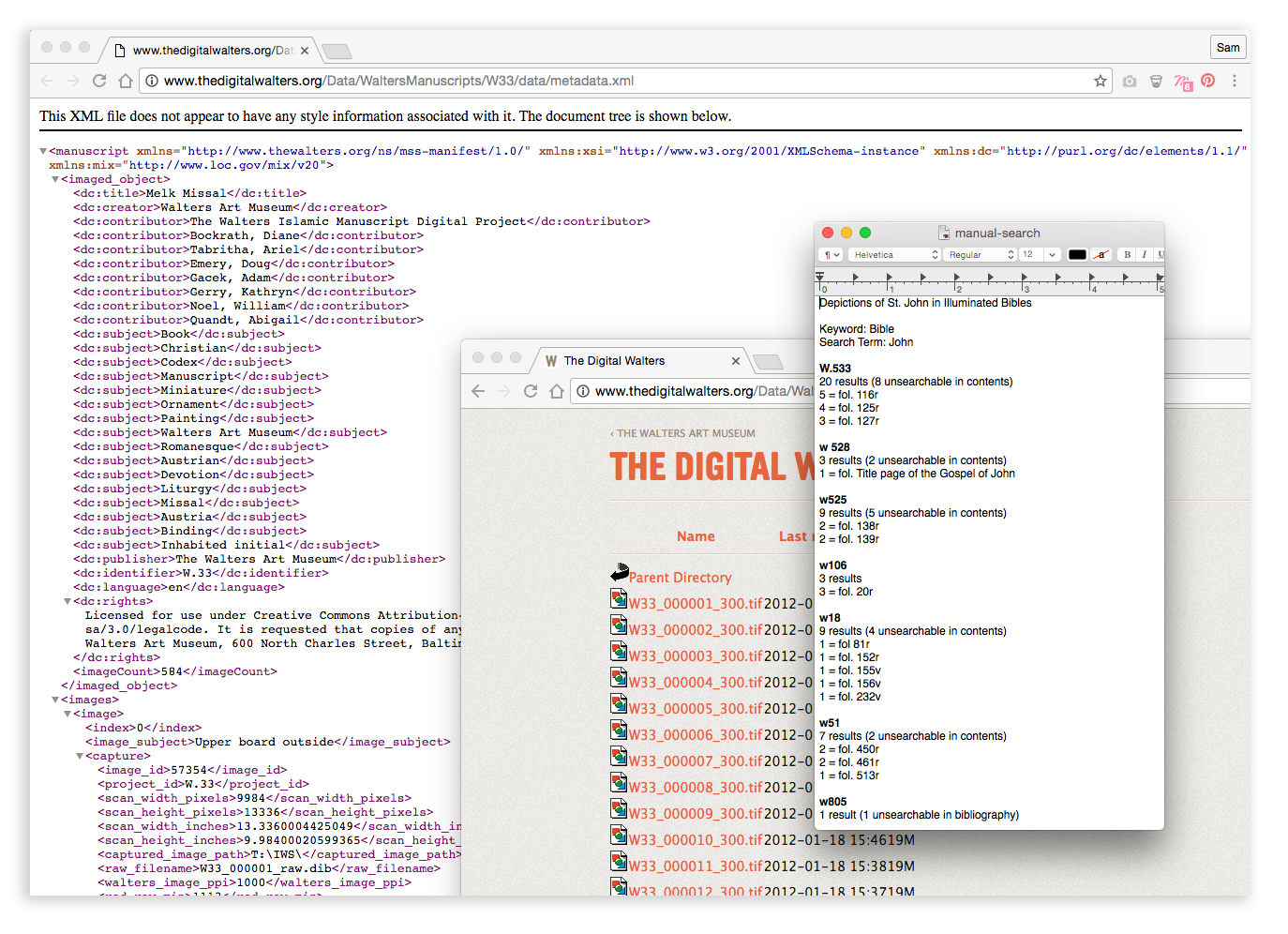

In my role as a UX designer, I found the need to do some pre-prototype data exploration, which would influence my wireframing (which would later become the prototype). The Walters wanted these manuscripts to be searchable via a custom keyword, like “dragon” or “cartography” or “King James”.

However I had the suspicion that it wouldn’t be quite so easy, because the text & tagging data surrounding any given manuscript was pretty limited. Getting 0 results in a search interface is pretty disheartening, so I started looking for alternatives.

I simulated a custom keyword search without taking any of my developers time by opening up those .xml files for each manuscript and using my trusty “Cmd+f” to find the frequency and location for any particular keyword. I put myself in the shoes of a researcher and started looking for certain common keywords, such as “John” (as in St. John of the Bible), or what I thought would be less common keywords, like “fox” (as in the Reynard in Dutch, English, French and German fables.)

What I found was more or less what I expected— custom keyword search was spotty, at best—, but I also made some unexpected discoveries. For example, there’s a text description for each illuminated folio (an illustrated couple of pages in a manuscript), which lends them to being easier to search with custom keywords. Yet, the categories & tags the museum created to organize all the manuscripts were applied at the manuscript level.

That meant folios themselves couldn't be filtered by tags, and entire manuscripts would be very difficult to search via custom keywords. By becoming aware of this early, we were able to design and code the interface so that these gaps in information didn't get in the way of users. You can see the result of this early manual data exploration online, where we blend custom keywords with pre-existing ones, making it quick and easy to add and remove both kinds of keywords to refine a search.

We’re excited to be a part of the launch of Walters Ex Libris because, not only are we proud of the work we’ve done, but we’re excited to see such valuable pieces of cultural history released for anyone and everyone to browse, research and enjoy.